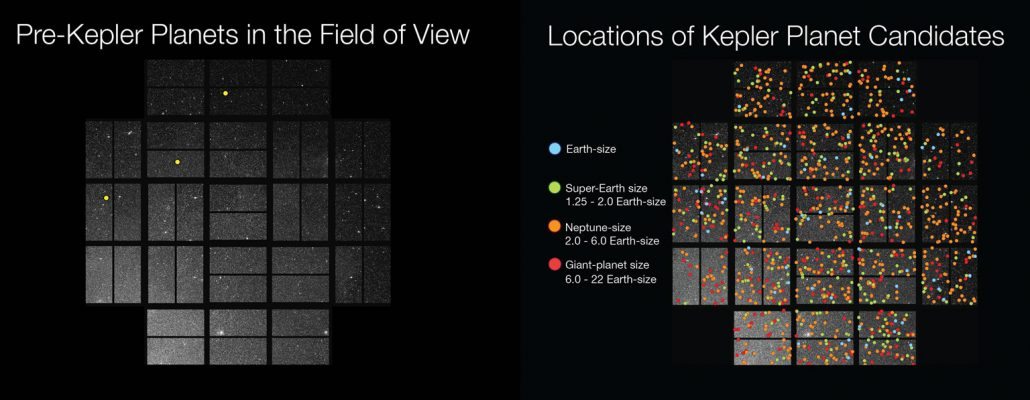

NASA’s Kepler mission has announced the discovery of 1,284 newly confirmed planets, raising the total confirmed exoplanets to more than 3,000. While this is a big step forward in exoplanet astronomy, it is also part of a shift in how exoplanets are discovered. That’s because these new planets weren’t discovered individually, but rather through an automated algorithm that gives candidate planets a statistical thumbs up or down.

The Kepler spacecraft discovers planets by measuring the varying brightness of stars in a small region of sky. As a planet passes in front of a star (such as the recent transit of Mercury) the star dims by a small but measurable amount. By watching for dips in brightness that repeat on a regular basis, astronomers can verify that a planet is orbiting a star.

In principle the process is straight forward, but in practice it can be extremely difficult. Stars have some natural variation in brightness due to things like solar flares, and starspots moving across the surface of a star can look quite similar to a transiting planet. So there is always the potential of getting a false positive. There have been instances where a planet was added to the list of confirmed exoplanets and then later removed upon further analysis. It takes careful analysis to distinguish a real planet from a poser, and it isn’t something that can be done quickly by hand. But Kepler has observed nearly 150,000 main sequence stars, and there it simply isn’t practical to go through all of that data by hand.

Enter statistical analysis. Rather than pouring over data by hand, a team of astronomers wrote a program to determine the odds of an exoplanet being a false positive, based on a comparison to known false positives. They had the program analyze data from more than 7,000 “objects of interest” in the Kepler data, which at first glance look like planetary transits. They found that about 2,000 of them had less than 1% odds of being a false positive. Some of these had previously been confirmed by other means, but 1,284 have not been confirmed previously.

Given the odds, it is likely that about 100 of these new exoplanets will later be outed as false positives. So it’s a bit misleading to say that exactly 1,284 new exoplanets have been confirmed. However the exact number isn’t important. This method allows us to narrow down the amount of exoplanet data. Now that exoplanets number in the thousands, we have to shift our methods away from sorting through data by hand and rely on statistical algorithms. And that’s an amazing shift. We have so much exoplanet data and so many exoplanet candidates that we can’t keep up. It’s a dramatic change from just two decades ago when only a handful of exoplanets were known.

Paper: Timothy D. Morton, et al. False Positive Probabilities For All Kepler Objects Of Interest: 1284 Newly Validated Planets And 428 Likely False Positives. The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 822, Number 2 (2016) DOI:10.3847/0004-637X/822/2/86